The Woman Who Defied Gravity: Gina Lollobrigida’s Flight in “Trapeze” (1956)

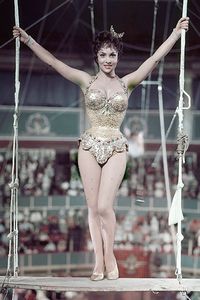

Under the grand dome of the Cirque d’Hiver in Paris, the audience held its breath. The orchestra’s brass section blazed to life, lights shimmered against sequined costumes, and a woman stepped onto a narrow wooden bar suspended high above the earth. Her balance was perfect, her gaze unwavering. The danger didn’t scare her—it thrilled her. The woman was

The film was Trapeze, directed by the Oscar-winning

When Trapeze was announced, Hollywood wasn’t sure what to make of its Italian leading lady. Lollobrigida had already gained attention in Europe for her sultry screen presence in Bread, Love and Dreams

Lollobrigida didn’t just meet those expectations—she shattered them.

Determined to prove herself, she trained for weeks on the trapeze under Lancaster’s guidance. A former circus acrobat himself, Lancaster demanded realism. He didn’t want doubles, he wanted authenticity—every drop of sweat, every gasp of risk. And Gina, who had grown up in the rugged hills of Italy and was no stranger to hard work, refused to back down. “They expected glamour,” she would later say, “but I gave them strength.”

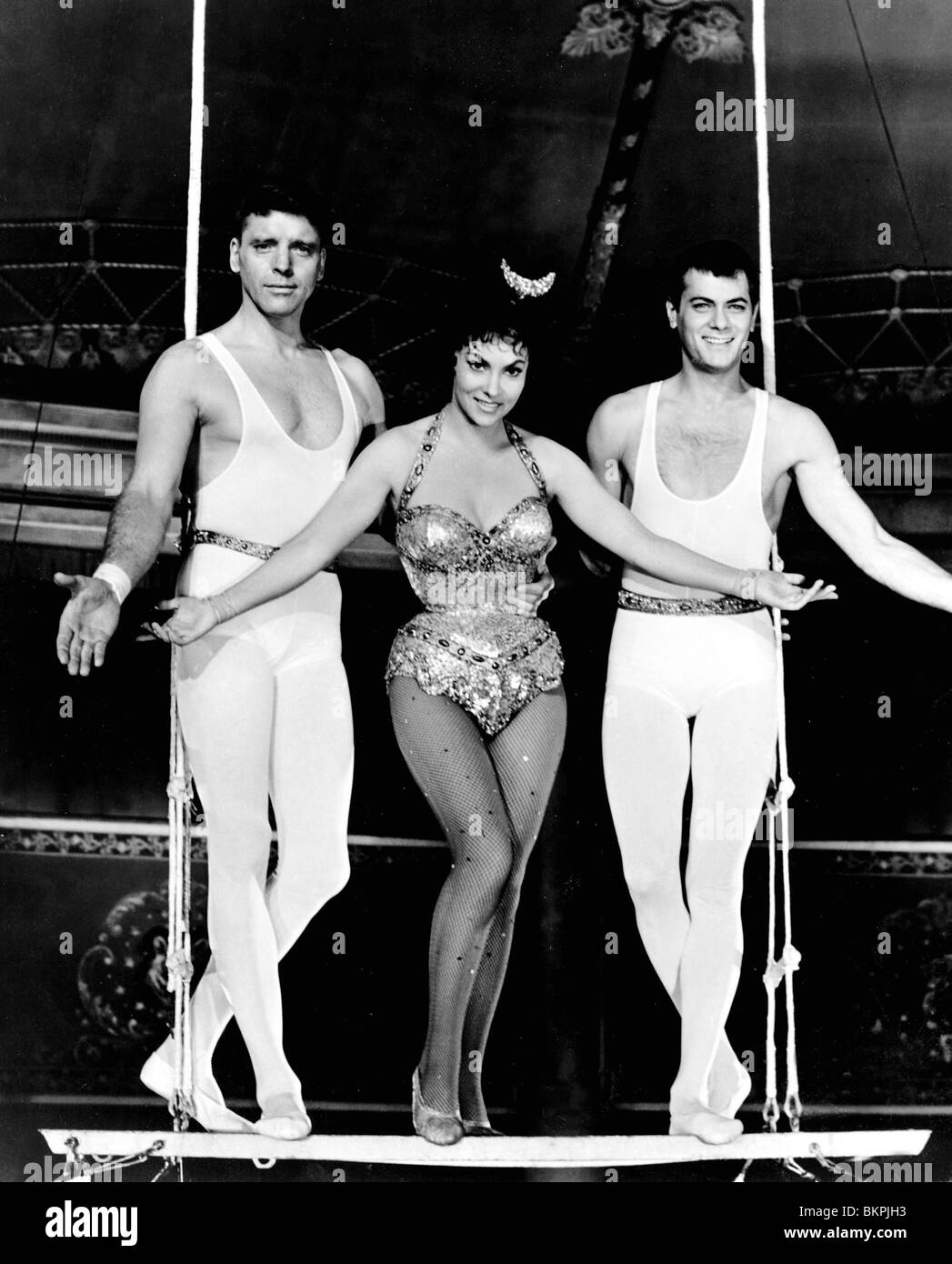

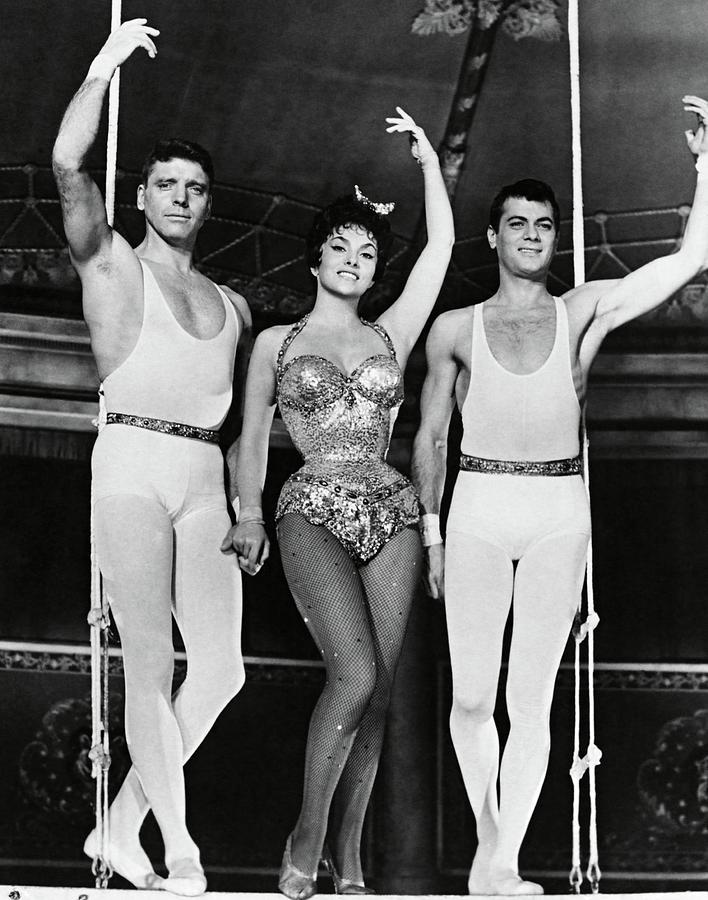

That strength burned through every frame. As Lola, the fiercely ambitious performer who enters the lives of two men—one a veteran trapeze artist recovering from a near-fatal fall, the other his daring young protégé—Lollobrigida brought fire and complexity to a role that could easily have been reduced to a cliché. Her Lola wasn’t just the romantic interest. She was the equal, the catalyst, the storm around which the others revolved.

Off-camera, the dynamic between Lollobrigida and her co-stars was equally charged. Lancaster, intense and commanding, was known for his perfectionism. Curtis, the young Hollywood heartthrob, was eager to prove his own worth in a film that demanded real physical skill. And in the middle stood Lollobrigida, who refused to be intimidated by either.

“There were moments,” she later recalled, “when the air between us felt electric—not romantic, but competitive. We were all fighting to stay on top, to give our best, to not fall—on the trapeze or otherwise.”

The tension was real, and it translated beautifully to the screen. Every glare, every smile, every movement carried the friction of pride and attraction. Critics would later say that the chemistry between the three wasn’t acting—it was instinct.

Filmed inside the historic Cirque d’Hiver, the production embraced authenticity to the point of recklessness. The performers dangled more than forty feet above the floor, often without safety nets. Lollobrigida, despite being terrified of heights, insisted on doing many of her own scenes. “You can’t fake courage,” she said. “You either have it, or you don’t.”

When Trapeze premiered, it became one of the biggest hits of 1956. Audiences around the world were captivated—not only by the heart-stopping stunts but by the emotional depth at its core. Here was a film about risk, not just physical but personal: the risk of ambition, of desire, of daring to want more than the world allows you.

And at the heart of it all was Gina Lollobrigida, shimmering under the lights yet grounded in something more powerful than beauty. She had crossed oceans and languages to claim her place among Hollywood’s elite, and she did it on her own terms.

For many women watching, she became a symbol of independence. While others were content to play the ingénue or the accessory, Lollobrigida portrayed a woman who was neither submissive nor cold—she was human, hungry, and real. “Trapeze,” said one critic, “belongs to Gina Lollobrigida the way the sky belongs to the bird.”

But the success of Trapeze was also a beginning. In the years that followed, Lollobrigida would continue to push boundaries. She moved fluidly between Hollywood and Europe, starring in Solomon and Sheba

By the 1970s, she reinvented herself yet again—this time behind the camera. She became a celebrated photographer and journalist, photographing luminaries such as Paul Newman, Audrey Hepburn, and Salvador Dalí. In one of her boldest moments, she even interviewed

“Beauty fades,” she once said, “but daring—daring lasts forever.”

Her words could easily describe her performance in Trapeze. Even today, still images from the film retain their hypnotic power: Lollobrigida suspended midair, her sequined costume sparkling like a constellation, her expression one of serene control. It is both a literal and symbolic flight—a woman who refused to stay on the ground, who claimed the space that had always been hers.

The magic of Trapeze wasn’t just in the spectacle of acrobatics. It was in what it represented: a moment in film history when artistry, courage, and sensuality collided. When a European actress dared to outshine her male counterparts not by playing their game, but by creating her own.

Decades later, Gina Lollobrigida’s name still evokes that same combination of glamour and grit. She was more than an actress. She was an artist, a dreamer, a force of will who rose—quite literally—above expectation.

Under the circus lights of 1956, she did more than perform. She soared. And long after the applause faded, the image of her suspended high in the air, caught between strength and grace, continues to remind us that the greatest act of all is to believe you can fly—then to prove it.

Why did Brigitte Bardot trade movie stardom for something far more radical?

In the glowing aftermath of World War II, France was a nation in flux—rebuilding its cities, redefining its identity, and reasserting its place in the world. Amid this transformation, cinema became not only an art form but a cultural mirror, reflecting the aspirations and contradictions of a country moving forward while still shadowed by its past. It was in this climate that Brigitte Bardot emerged. By the mid-1950s, she was not simply an actress or a model; she was a phenomenon, a lightning bolt that struck both the French screen and the global imagination. With her tousled blonde hair, her aura of unstudied sensuality, and a rebellious spirit that felt almost untamed, Bardot challenged conventions and redefined what it meant to be a woman in film.

Born Brigitte Anne-Marie Bardot in Paris in 1934, she was raised in a comfortable bourgeois family. Her early years were shaped by discipline and tradition—her mother enrolled her in ballet lessons, and Bardot trained rigorously at the Conservatoire de Paris. Ballet gave her poise, grace, and an awareness of her body that would later become essential to her on-screen magnetism. Yet, at the time, she had no grand ambitions of stardom. A chance modeling opportunity brought her to the cover of Elle magazine at just fifteen years old, and from there, the camera never let her go. Casting directors noticed her immediately, and Bardot’s transition from ballet to film seemed almost effortless, though in reality it was a leap from the structured world of classical dance into the unpredictable, often exploitative realm of cinema.

.jpg)

Her early films in the 1950s gave glimpses of her natural charm, but it was Et Dieu… créa la femme (And God Created Woman, 1956) that changed everything. Directed by her then-husband Roger Vadim, the film presented Bardot not as a polished Hollywood-style starlet but as a free-spirited young woman unafraid of her desires. Her sun-kissed skin, loose blonde hair, and unfiltered sexuality scandalized conservatives and thrilled younger audiences who saw in her a new kind of freedom. Bardot’s character in the film—wild, unapologetic, and resistant to social constraints—felt dangerously modern. She wasn’t playing an ingénue or femme fatale; she was embodying a revolution, one that blurred the line between role and reality. The film made Bardot an international sensation and cemented her as the face of a new era of liberated femininity.

By the 1960s, Bardot was not just a film star—she was the embodiment of French style, spirit, and rebellion. Unlike Hollywood actresses who were often carefully packaged by studios, Bardot’s appeal was her lack of artifice. She walked barefoot through the streets of Saint-Tropez, a fishing village that she transformed into a playground for artists, musicians, and dreamers. The town, once quiet and provincial, became synonymous with bohemian glamour largely because of her presence. Fashion followed her lead: off-the-shoulder tops, tousled beach hair, and natural makeup became global trends thanks to her effortless, seemingly spontaneous choices.

Her influence extended beyond cinema and fashion. Bardot recorded music, most famously collaborating with Serge Gainsbourg on sultry songs like “Harley Davidson” and “Bonnie and Clyde,” which added to her aura of playful rebellion. She became an international muse, inspiring not only designers and musicians but also writers and intellectuals who saw in her a challenge to traditional notions of femininity. Bardot was admired, imitated, and endlessly analyzed, though often in ways that failed to capture her complexity.

Yet fame came with a cost. Bardot herself often expressed frustration at being reduced to her appearance and sexuality. Critics dismissed her as a “sex kitten,” ignoring the intelligence and agency with which she navigated her career. While many saw her as a symbol of liberation, Bardot sometimes felt trapped by the very image that made her famous. Unlike many actresses who fade gradually from the spotlight, she made a decisive, shocking choice: in 1973, at just thirty-nine years old and still one of the most recognized women on the planet, she retired from acting altogether. To her admirers, this decision seemed unthinkable. But to Bardot, it was an act of self-preservation and autonomy. She refused to be consumed by the machine of fame, choosing instead to redirect her life toward causes that mattered more deeply to her.

Her post-cinema chapter became just as defining as her screen career. Bardot devoted herself passionately to animal rights, founding the Brigitte Bardot Foundation in 1986. With characteristic fearlessness, she campaigned against animal cruelty, fur industries, seal hunting, and factory farming. She lobbied governments, donated personal wealth, and used her fame not for self-promotion but to amplify the voices of the voiceless. In many ways, this transition from movie star to activist represented the ultimate reinvention: Bardot showed the world that celebrity could be repurposed as a tool for real, tangible change.

This shift also redefined her legacy. No longer was she only the screen siren of the 1950s and 1960s; she became a cultural figure whose life told a larger story about independence, choice, and courage. Her retirement from film wasn’t a retreat—it was a declaration that she would not be confined by others’ expectations. In doing so, she demonstrated a radical kind of strength, one that continues to resonate with women who refuse to be defined solely by external perceptions.

Today, Bardot stands as something far greater than a movie star. She represents an era when women began pushing against the boundaries of how they were seen and what they were allowed to be. Her life is a reminder that beauty and glamour, while powerful, are not the sum of a woman’s worth. Reinvention, conviction, and courage can be even more lasting. She once said she wanted to “give her life to animals,” and in doing so, she gave the world a different example of stardom—one rooted not in endless self-display but in advocacy and purpose.

More than six decades after her rise to fame, Brigitte Bardot’s influence remains undeniable. She shaped fashion, inspired liberation, and challenged cinema. She embodied the carefree spirit of Saint-Tropez, the sensual defiance of post-war Europe, and the determination of an individual unwilling to be caged by public expectation. Her journey from ingénue to global star, from sex symbol to activist, is not just the story of a woman—it is the story of a movement.

Brigitte Bardot wasn’t just a star of the screen. She was, and continues to be, a force—an icon of beauty, freedom, and reinvention whose legacy endures far beyond cinema.